Stay home from work. Eat a feast with good friends. Dance and Sing. Raise a toast to the thousands who have gone before, struggling for freedom & equality in the face of violence & oppression.

**************************************************************

From the Wikipedia entry for Howard Fast:

Fast spent World War II working with the United States Office of War Information, writing for Voice of America. But he had joined the Communist Party USA in 1944, and was called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. He refused to disclose the names of contributors to a fund for a home for orphans of American veterans of the Spanish Civil War (one of the contributors was Eleanor Roosevelt), and he was imprisoned for three months in 1950 for contempt of Congress.

It was while he was in jail that Fast began writing his most famous work, Spartacus, a novel about an uprising among Roman slaves. Blacklisted for his Communist activities and his criminal record, Fast was forced to publish the novel by his own Blue Heron Press. Unable to publish under his own name, he used various pseudonyms, including E.V. Cunningham, under which he published a series of popular detective novels starring a Nisei detective with the Beverly Hills, California Police Department.

In 1952, Fast ran for Congress on the American Labor Party ticket. During the 1950s he also worked for the Communist newspaper, the Daily Worker. In 1953, he was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize. But, later in the decade, Fast broke with the Party over issues of conditions in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

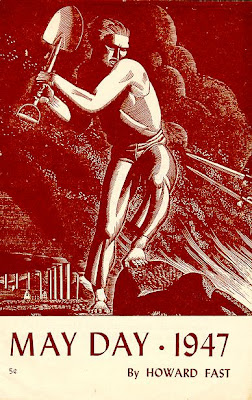

May Day - 1947

by Howard Fast

This is a tale

. . . but not for all of you! Only for those of you who love life, and who would live it as free men. Not for all of you, but for those of you who hate injustice and wrong, who find no good in starvation, misery and homelessness. For those of you who remember when twelve million unemployed looked hollow-eyed into the future.

For those of you who have heard the whimper of a child in hunger, or a man in pain. For those of you who have heard the guns and listened for the smack of the torpedo. For those of you who saw the dead that fascism made. For those of you who made the sinews of war and were given, as payment, the nightmare threat of atomic death.

It is a tale for those. For mothers who would rather see their children live than die. For workers who know that the fascist breaks unions first. For veterans who know that those who make the wars do no fighting. For students who know that freedom and knowledge are inseparable. For intellectuals, who must die if fascism lives. For Negroes, who know that Jim-crow and reaction are two sides of the same coin. For Jews, who learned from the gentle Hitler what anti-Semitism really is. And for children, for all children, for the children of every color, every race, every creed – for them, this tale is written, so that they may look forward to life and not to death.

This is a story of the strength of the people, of their own day, which they chose, and upon which they celebrate their unity and strength. It is a day which, to our lasting pride, was the gift of the American working class to the world.

They did not tell you

. . . in the histories you studied in school how May Day began, but there is much that was noble and brave in our past that the histories carefully blot out. It goes that May Day is a foreign importation, but to the men who made the first May Day in Chicago in 1886, there was nothing very foreign about it. They spun it out of native yarn; their anger at what the wage system does to human beings did not have to be imported.

The first May Day took place in Chicago in the year 1886. There was a prelude to it, a picture worth recalling. For a decade before 1886, the American working class was in a process of birth and growth, and it was by no means a bloodless process. The young nation which had swept from ocean to ocean in so short a time, built cities, spanned the plains with railroads, and laid low the virgin forests, was now on the way to becoming the first industrial land. And in doing so, it turned upon those who had done the work, built with their hands all that was America, and squeezed the very life from them.

Men, women, and children too, were literally worked to death in the new American factories. The twelve hour day was a commonplace, the fourteen hour day not rare, and in many places even children worked sixteen and eighteen hours a day. Wages were low, very often well below the basic subsistence level, and mass unemployment began to come with the bitter regularity of cyclical depression. Government by injunction was the order of the day.

But the American working class was not docile. It did not accept this and bear it as its natural lot; it fought back – and it taught the entire world a lesson in worker's militancy that has no parallel, even to this day.

In 1877, a railroad strike started in Martinsburg, West Virginia. The militia was called out, and after a brief battle with the workers, the strike was suppressed – but only locally; the spark ignited turned into a flame. The Baltimore and Ohio went out; the Pennsylvania went out, and then railroad after railroad, until the tiny local eruption had turned into the greatest general rail strike the world knew up to then. Other industries joined in, and in many areas the rail strike became a general strike.

For the first time, the government as well as the bosses became aware of what the strength of labor can mean. They called out the militia and the regular army; vigilantes were deputized. In some places, pitched battles were fought. In St. Louis, civil authorities abdicated, handing the city over to the administration of the working class. No one can calculate today what the casualties were in that violent outburst, but that they were enormous no one who has studied the facts can doubt.

The strike was finally broken, but American labor stretched and breathed with new awareness. The birth pains were over, and the coming of age had begun.

The next decade was a period of struggle, at first struggle for survival out of which grew the struggle for organization. The government did not easily forget 1877; armories began to be built in various American cities; main streets were broadened, so that gatling guns could command them; a mass anti-labor private police organization, the Pinkerton Agency, came into being; and measures against labor became more and more repressive. The red menace, which had been used as a propaganda weapon in America since the 1830s, was now built into the full-scale bogeyman we see today.

But the workers did not take this supinely. In turn, they organized. The Knights of Labor, born underground, had, by 1886, more than 700,000 members. The young American Federation of Labor, organized as a voluntary association of unions with socialism as one of their goals, was growing rapidly, class-conscious, militant, and relentless in its demands. A new slogan had come into being, a new demand, clear, unequivocal:

"Eight hours of work, eight hours of sleep, eight hours of recreation."

By 1886, American labor was a young giant, ready to try its strength. The armories were built, but the armories were not enough. The Pinkertons were not enough, nor were the gatling guns. Organized labor was on the march, and its single militant slogan echoed across the land – and the earth, too:

"Eight hours of work a day--no more!"

At that time, in 1886, Chicago was the center of the militant, left-wing labor movement. It was in Chicago that the idea was born for a united workers' demonstration, a day that was theirs and no others', a day when they would lay down their tools and shoulder to shoulder demonstrate their strength.

The First of May was chosen as the day of the working class, the people's day. Well in advance, an Eight Hour Association was formed to prepare for the demonstration. This Eight Hour Association was a united front, formed out of the American Federation of Labor, the Knights of Labor and the Socialist Labor Party. Also allied with them was the Central Labor Union of Chicago, which included the most militant left-wing unions.

It was no small thing that began there in Chicago. 25,000 workers attended a pre-May Day mobilization. When May Day itself came, the Chicago workers poured from the shops by the thousands, laying down their tools, marching and gathering at mass meetings. Even that, at its inception, thousands of middle class people joined with the workers, and this pattern of solidarity was repeated in many other American cities.

Then, as now, big business struck back – with bloodshed, terror, and judicial murder. A mass meeting two days later at the McCormick Reaper Works, which was on strike, was attacked by the police, and six workers were murdered. When the workers demonstrated, in protest of this unspeakable action the next day at Haymarket Square, the police attacked again. A bomb was thrown, killing several police and workers – and though it was never discovered who threw the bomb, four American labor leaders were hanged, for a crime they did not commit, and of which they were proven innocent.

As one of these brave men, August Spies, stood on the gallows, he cried out:

"There will come a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today."

How true that is time has proven. Chicago gave May Day to the world, and on this, the sixty-second May Day, the people of the world, assembled in the might of all their millions, bear out August Spies prediction.

It was three years after the Chicago demonstration that working-class leaders from all over the world assembled in Paris to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the fall of the Bastille. One after another, the leaders of the various nations spoke.

Finally, it was the turn of the Americans. The worker who represented our working class rose, and in simple and straightforward language, he told the story of the struggle for the eight-hour day which culminated in the shameful Haymarket incident of 1886.

He painted a picture of violence, bloodshed, and brave gallantry that the delegates to that convention remembered for years afterwards. He told how Parsons had gone to his death, after being offered life if he would only separate himself from his comrades and plead for clemency. He told how ten innocent Irish miners were hanged in Pennsylvania because they had fought for the right to organize. He told of full scale battles where the workers fought armed Pinkertons, and he told much more. When he had finished, the Paris Congress adopted the following resolution:

"The Congress decides to organize a great international demonstration, so that in all countries and in all cities on one appointed day the toiling masses shall demand of the state authorities the legal redaction of the working day to eight hours, as well as the carrying out of other decisions of the Paris Congress. Since a similar demonstration had already decided upon for May 1, 1890, by the American Federation of Labor . . . this day is accepted for the International Demonstration. The workers of the various countries must organize this demonstration according to conditions prevailing in each country."

So it was done, and May Day belonged to the world. Good things belong to no one people or nation. As the workers of country after country fitted May Day into their lives, their struggles and their hopes, they came to take for granted that the day was theirs – and that too is right, for of all nations on the face of the earth, we are most surely the nation of nations, the combination of all peoples and all cultures.

What of this May Day?

The May Days of the past light up the struggles of half a century like beacons. It was on May Day at the turn of the century that the working class first condemned imperialist aggrandizement. It was on May Day that workers marched in support of the infant socialist state the Soviet Union. It was on May Day that we celebrated, in all our strength, the organization of the unorganized.

But no May Day in the past ever faced so ominous and yet so hopeful a future as the May Day we inaugurate now. Never before was there so much to be won; never before was there so much to be lost.

It is not easy for the people to speak. The people do not own the press, or the pulpits, nor do the majority of our delegated representatives in government serve the people. The radio does not belong to the people, nor are the motion pictures theirs. Big business monopoly control is well established, very well established – but the people themselves belong to no monopoly.

The strength of the people is their own, and May Day is their day – to show that strength.

There is a loud voice in the marching of millions. It is time that those who would hand America over to fascism heard that voice!

It is time for us to let them know that real wages have dwindled by almost fifty percent, that larders are empty, that here in America more and more people are feeling the pinch of hunger.

It is time to raise our voices against the anti-labor legislation, the two hundred and more anti-labor bills coming up in Congress – bills that would open the field to smash labor as surely as Hitler's Nazism smashed German labor.

It is time for organized labor in America to wake up to this fact – to the desperate eleventh hour need for labor unity – before it is too late and no organized labor remains to be unified.

You read here a tale of men who worked twelve and fifteen hours a day, of government by terror and injunction.

That is the goal of those who seek to smash labor today. Those are the good old days they would revive, as proven by the Supreme Court decision in the United Mine Workers' case. You will give them your answer when you march on May Day.

It is time that we recognized what the call for an American empire means, for intervention in Greece, Turkey and China. What is the price of Empire? Let those who scream for America to save the world by ruling the world look at the fate of other empires! Let them count the cost of war, in lives as well as money.

It is time we woke up to what the anti-Communist witch hunt means! Was there ever a land in which the outlawing of the Communist Party was not the prelude to fascism? Was there ever a land where the labor unions were not smashed just as soon as the Communists were disposed of?

It is time we became aware of the cost of things! The price of Red-baiting is the destruction of organized labor – and the price of that is fascism. And who is there today who will not recognize that the price of fascism is death?

For almost a hundred years, organized labor has been the backbone of American democracy. Now, evil and sinister forces are determined that organized labor must be destroyed.

May Day is the time for all liberty-loving citizens of this land to answer the reactionaries. There is a loud voice in the marching of millions! Join with us in the May Day demonstration, and give your answer to the merchants of death.

Fun literary fact about Howard Fast: his son Jonathan married Erica Jong and is the father of her daughter Molly Jong-Fast. All writers.

ReplyDelete